March by John Lewis

March: Book One by John Lewis, Andrew Aydin, and Nate Powell

Reviewed By: Sariah Amin, Kenny Coleman, Christian Bazinet, and Juana Apodaca

Book Review

Voice’s ability

to diversify in the way it is expressed and proliferated in mobilization, proves

consistently to be a crucial asset for human success. In March: Book One, authors John Lewis, Andrew Aydin, and Nate Powell

explore the way that nonviolence was used to make a bold statement during the

civil rights movement. The story revolves primarily around John Lewis’s

experiences throughout this historic time.

Originally from

the southern state of Alabama, Lewis grew up on a farm in Troy. He was educated

largely at the American Baptist Theological Seminary, and contributed a great

deal to the civil rights movement by leading nonviolent protests. He was even a

part of the March on Washington. Lewis eventually put his name on the ballot

for U.S. Representative of Georgia. He won and has acted in that role since 1987.

The incumbent Representative has written two self-help books, one memoir, and

four graphic novels.

By delving into

the woes of the underrepresented in this specific book, Lewis seeks to document

the efficacy of placing a social magnifying glass and bullhorn to the voices

owned by those underrepresented—the cruelly ignored. The leaders of the civil

rights movement worked to show that

these peaceful, quiet voices were objectified loudly and violently at times.

There are also symbolic add-ins that teach the righteousness of representing

the oppressed. As the book moves from the life of an early John Lewis to that

of the congressman, the authors use young Lewis’s relationship with his farm

chickens as a metaphorical focal point for the entire story. In this section,

Lewis is introduced to two aspects that will eventually converge and inspire

his life’s work. It becomes apparent that he develops a tenderness for the

animals at a time when he also becomes inclined to read the Bible. He would

preach to them and for them. This act of reading awakens a hunger for knowledge

in him, and so leads the way to personal and political success.

Formatted as a

graphic novel, Lewis wishes to reach an audience close in age to the young

preacher of chickens himself—middle school/high school. Illustrated by Nate Powell, the design and layout

of the novel accents many of the nuances in Lewis’s story. Choosing to

illustrate in black and white is dramatic and makes obvious implications of the

times that Lewis was a part of. In addition to color, Powell creates dynamic

visuals by capturing and directing many snapshots of movement and action. This

is also emblematic of the time. It is not just the characters and figures in

the novel constantly in some sort of motion—physically or emotionally. The use

of slanted lines to build the frames moves the story along as much as the words

do. He also has a way of intermingling frames amongst each other in order to

create an impression of image unity.

The idea of a

dynamic and ever-present human voice exemplifies itself neatly in this young

adult graphic novel. In the larger voice of social reform, persistence is a

propelling factor. One small but mighty idea recurs throughout the novel—the

evolution of voice transportation. Tools meant to convey voice are presented

throughout the novel: the mailbox, the newspaper, the stationary phone, and

finally the cell phone. The last device is extremely effective at spreading

information like wildfire. In the book, there are multiple images of John

Lewis’s cell phone, notably the one at the end. Most times, things need to be

“heard” many times and in many different ways before they really mobilize. John

Lewis’s novel is a stack of pages worth looking over at least once.

|

John Lewis, born on February 21, 1940 in Alabama, lived his childhood

helping his parents as sharecroppers in the South during the era of segregation

including the legal practices of it via Jim Crow laws. By the time he grew to

his teenage years and into adulthood at Fisk University, Lewis had organized

and participated in several nonviolent sit-ins and other anti-segregation

events. He was a participant in the famous Freedom Rides in the South as well.

By the mid-1960s Lewis became the chairman for the Student Nonviolent

Coordinating Committee (SNCC), and organization he had helped form beforehand.

He also was one of the speakers at the March on Washington in August of 1963,

where Martin Luther King Jr. gave his famous “I Have a Dream” speech. As

chairman of the SNCC, Lewis cooperated with others in the committee to organize

voter registration drives and other such community-oriented activities

particularly to help African Americans push for the rights they believed they

had the right to have even in their historical context. Alongside Hosea

Williams, Lewis helped gather African Americans for the march across Edmund

Pettus Bridge to demand voting rights in Montgomery that ultimately led to

state law enforcement becoming excessively brutal toward the participants and

infamously became known as “Bloody Sunday.” Ultimately, protests and other such

actions similar to Lewis’s march in 1964 pressured the passing of the Voting

Rights Act of 1965. Even after several assaults against him and being arrested

a few times, Lewis still advocated for nonviolence as a method of demanding and

gaining rights that segregation laws especially kept certain people away from.

After leaving the SNCC in 1966, Lewis began to take his turn toward

politics as a career. Straight out of SNCC, Lewis continued to be involved in

the Southern Regional Council’s practices surrounding voter registration. He

also became the Direction of the Voter Education Project (VEP) which assisted

four million individuals to be registered to vote. A decade later in 1977,

Lewis receives recognition from then President Carter in the form of being

placed to help a federal volunteering agency. It was not until 1981 that Lewis

became a politician himself when the Atlanta City Council elected him. Early is

his political career Lewis predictably stood up for ethics in government and

the preservation of neighborhoods. Five years later in 1986, Lewis was elected

as the representative in Congress for the Fifth Congressional District of

Georgia. In Congress, Lewis is a member of the House Ways & Means Committee

and its Subcommittee on Income Security and Family Support as well as being

part of the Subcommittee on Oversight. John Lewis also has won various awards

including the Medal of Freedom from President Obama, the Lincoln Medal from

Ford’s Theatre, the Martin Luther King Jr. Non-Violent Peace Prize, the only

John F. Kennedy “Profile in Courage Award”, and others.

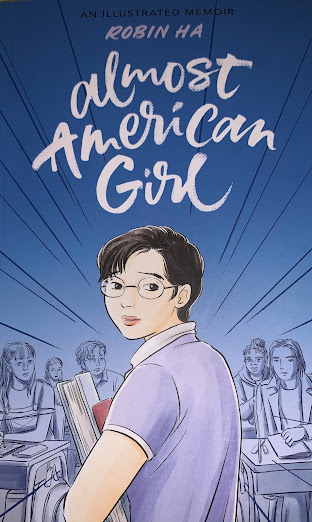

As far a March goes, Lewis

co-authored the graphic novels that are autobiographical in nature. Book one

received a 2014 American Library Association (ALA) Coretta Scott King Book

Award Honor, an ALA Notable Children's Book Designation, and was named one of

YALSA's 2014 Top Ten Great Graphic Novel's for Teens. Book two and three of the

series are similarly awarded as well.

Online Materials:

1). “We Shall Overcome--Selma- to-

Montgomery March.” National

Park Service. NPS.Gov.

This article will inform students how civil

rights leaders and marchers, including John Lewis, were physically hurt on “Bloody

Sunday” in Selma, Alabama. They were

marching for African American's right to vote. Shortly after Martin Luther King

Jr. led the march down the bridge, they won the right to vote (Voting Rights

Act 1965). Through this history, students will see the significance of the

depiction of “Bloody Sunday” in the introduction of the graphic novel.

2) Video. “Bloody Sunday 1965 With John Lewis Interview.” YouTube, YouTube, 30 May 2012.

This video is a more emotional interview,

with John Lewis, about what happened on Bloody Sunday. There are images and

clips of the event in it, too. John Lewis states how about 600 marchers got as far as the Edmund Pettus

Bridge before they were attacked with clubs and tear gas by their own

government. Due to the severe injuries Lewis suffered by the state and local

lawmen, he had to be hospitalized. After watching John Lewis speak, students

will understand how important the right to vote was for African Americans.

Hundreds of people risked their lives for it. Students can then look back at

the pictures of it in the novel, and understand the true bravery of the

marchers.

3). “The Do’s and Don’ts of a

Nonviolent Sit-In Movement.” Oprah’s Master Class, OWN, 15 January 2017.

In this short video and summary, John Lewis

describes what he taught activists when people became violent at their

nonviolent sit in movements. Because their movement was for social reform and

justice, they needed to make the community believe it was a cause to

support. Lewis said not to fight back

when people attacked them. By not fighting violence with violence, Lewis

explains, the community would view their movement as respectable. Their peace

would promote change. Students will then read the novel understanding that people ended up reacting favorably to John Lewis’ nonviolent movement because they

were peaceful.

|

4). Wallenfeldt, Jeff. “John Lewis- American Civil Rights Leader and Politician.” Encyclopaedia Britannica, 14 February 2018.

This article is a biography of the life and accomplishments of John Lewis. i.e. Chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). He played a key role in the historic march on Washington. He is considered one of the Civil rights movements ‘Big Six’ leaders. In 2002 he was awarded NAACP Spingarn Medal. His accomplishments go on. Through this article, students will see how influential Lewis was to the Civil Rights Movement and for all oppressed people

5) Parry-Giles,

Shawn. “John Lewis. ‘Speech at the March

on Washington’ (28 August 1963).”

Voices of Democracy: The U.S. Oratory

Project.

This document

is the speech, for jobs and freedom John Lewis gave before making the historic

march on Washington. It was given in Washington D.C., the 28th of August 1963.

In the speech, Lewis eloquently articulates how African Americans cannot keep

waiting for their civil rights. Too many people have been hurt and killed

waiting. The march on Washington is a step closer towards that change. After

reading this speech, students can reflect and discuss the laws and social

changes that enabled African Americans jobs and freedom.

6). “Introduction to the Civil Rights

Movement.”

Khan Academy, khanacademy.org.

This article is an overview of all the

events that took place before, during, and after the Civil Rights Movement. It will

help give students a breakdown of what the Civil Rights Movement accomplished

and how it still influences American people today. It will also help students

understand the context of Lewis’ et. al graphic novel.

7) Novkov,

Julie. “Segregation (Jim Crow).”

This article gives students a brief history of segregation and Jim Crow laws in 16

U.S. states from the 1880’s to the 1960’s . It will specifically show students

where black and white people were segregated in public and private places,

within these states. This article will allow students to view the racist laws

John Lewis was moving against.

8).Standring,

Suzette Martinez. “Civil Rights Icon John Lewis: Love

and Nonviolent Protest.” Suzette Martinez Standring.

Readsuzette.com, 27 April 2017.

This article will show students how John

Lewis was positively influenced by John F. Kennedy, Robert Kennedy and Martin

Luther King Jr. In the article, Lewis

talks about how their accomplishments influenced him to be involved in politics and run for

office. This article can be used to strengthen students' understanding of how Lewis became involved in politics.

9). Video. “ 2016 National Book Award Winner: Rep. John Lewis (Young

People’s Literature).”

YouTube, YouTube, 17 November 2016.

John Lewis Receives the 2016 National book Award for

Young People's Literature, for book 3 of the March trilogy. His award and numerous accomplishments shows

students how far African Americans have come since the 1960’s. Students can discuss, for example, how John Lewis was not allowed in public libraries for being black, prior to the Civil Rights Movement.

Ima

Common Core Standards

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RL.9-10.1

Cite strong and thorough textual evidence to support analysis of what the text says explicitly as well as inferences drawn from the text.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RL.9-10.2

Determine a theme or central idea of a text and analyze in detail its development over the course of the text, including how it emerges and is shaped and refined by specific details; provide an objective summary of the text.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RL.9-10.3

Analyze how complex characters (e.g., those with multiple or conflicting motivations) develop over the course of a text, interact with other characters, and advance the plot or develop the theme.

Activity

Lesson Plan

During the course of a week, students will be expected to read March by John Lewis. This will be done on their own time, the week prior to instruction. After the week allowed for reading is complete, students will spend the following week learning about and discussing the novel in small groups, and as a class. They will be expected to show up to class on the first day of the new week, ready to begin working on the Character Analysis Chart handout. The handout will be completed in small groups throughout the course of two days. On the first day, students will be expected to complete the “Who” section of the chart, in addition to developing two ideas for “What” and two ideas for “Why”. The “Who” section is to give a brief summary of the student’s understanding of who John Lewis is based on the context of the novel. The “What” section is to refer to specific events that occurred throughout the novel, particularly those John Lewis’s character was involved in. The “Why” section is to explain, from the student’s understanding, why those events are of significant importance in the novel. This will work on fulfilling Common Core Standard 9-10.3. After being given class time to complete the assigned sections, students will discuss the novel, as well as their charts, with the rest of the class. On day two, students will be given class time to get into their small groups and come up with three more ideas for “What” and three more ideas for “Why”. Upon completion of the chart, each group will randomly be assigned a theme the teacher has found to be significant throughout the novel, and the remainder of the class time will be spent discussing the novel and Character Analysis Charts as a class. The following day, students will get into their groups and begin discussing the theme they were assigned. This will work on fulfilling Common Core Standard 9-10.2. Students will then be given the class period that day, as well as the following day, to complete a Prezi, in which they present their theme and show where in the text they found it to be most prominent. Students are to essentially use textual evidence to prove the importance of their assigned theme, fulfilling Common Core Standard 9-10.1. After the two days allowed for group work have passed, students are to spend the fifth and final day of the week sharing and presenting their Prezi’s with the rest of the class.

Bibliography:

“Biography.” Congressman John Lewis, 28 June 2016, https://johnlewis.house.gov/john-lewis/biography

“John Lewis.” Biography.com,

A&E Networks Television, 19 Jan. 2018, www.biography.com/people/john-lewis-21305903.

Waggoner, Cassandrea. “Lewis,

John R. (1940-).” The Black Past:

Remembered and Reclaimed, https://blackpast.org/aah/lewis-john-r-1940.

Images Bibliography:

Images Bibliography:

Congressman John

Lewis awarded Medal of Freedom in 2011. obamawhitehouse.

Feb. 27, 2011. https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/blog/2011/02/17/exclusive-video-presidential-medal-freedom-recipients-their-own-words

“I preached to my

chickens”: CBLDF. Feb. 7, 2014. http://cbldf.org/2014/02/using-graphic-novels-in-education-march-book-one/

John Lewis, Andrew

Aydin, and Nate Powell at Comic-Con 2015: The Horn

Book. Aug. 8, 2016. https://www.hbook.com/2016/08/five-questions-for-john-lewis-andrew-aydin-and-nate-powell/

“John Lewis is a

genuine American hero”: Congressman John

Lewis. June 28, 2016. https://johnlewis.house.gov/john-lewis/biography

Lewis in 1964: National Park Service. Sept. 4, 2013. https://www.nps.gov/subjects/civilrights/john-lewis.htm

‘March: Book One’:

The National Memo. Aug. 29, 2014. http://www.nationalmemo.com/excerpt-march-book-one/